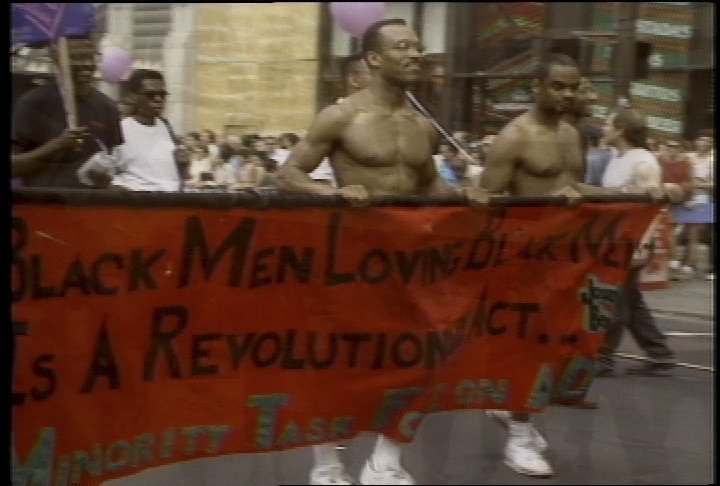

I can’t even begin to imagine how the men in the Marlon Rigg’s Tongues Untied (1989) would have reacted if somehow they were told that in 2017 a coming-of-age film about a gay, black man would win the Best Picture category at the Academy Awards.

I strongly believe that Marlon Riggs would have replied that – black men loving black men is a revolutionary act.

He was right when he said it then, and it’s right to be said now. This statement doesn’t apply just to the gay community, and it doesn’t apply to just the black community (although representation on both of those fronts deserves acknowledgement). He’s speaking to the people who exist feeling the pressure to straddle both and at the same time not be fully represented in either.

As Catherine Squires discussed in her essay “Rethinking the Black Public Sphere: An Alternative Vocabulary for Multiple Public Spheres” – counterpublics are born from the marginalization and uncaring attitudes towards problems that don’t affect the people who make up the largest majority. The main “public” they refer to are the straight, cis, middle-class, white men that dominate our society and say they speak for the ‘people’ and by people, they mean, their people. Straight, cis, middle-class, white men.

The gay, black men represented in both Tongues Untied and the film Moonlight (Berry Jenkins, 2017) represent a counterpublic within counterpublics. Not only were (and are) they fighting for representation in a world dominated by straight, white, middle-class men, they’re fighting for representation within a black community that is dominated by straight activists, and a gay community dominated by white activists. The messy spiral of categories and subcategories of counterpublics that Squires forewarned is a reality for gay, black men, and just because it’s often overshadowed by larger movements doesn’t make their issues and lack of representation any less important for the people who identify within those groups. A black man on TV isn’t the same as a gay, black man on TV, just the same as a gay man in a movie isn’t the same as a black, gay man in a movie.

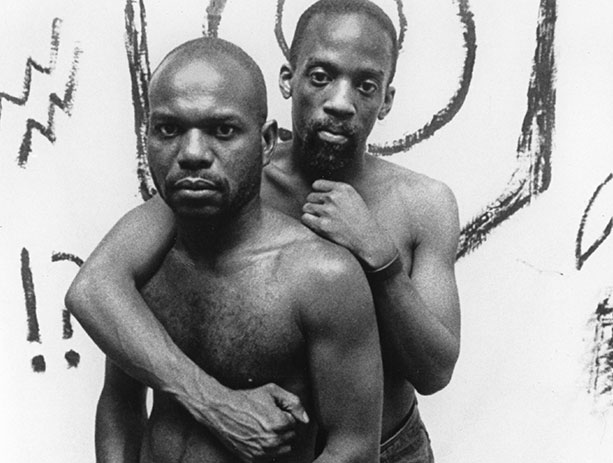

Despite all of the pessimism, fear, and stigma that have followed and surrounded gay, black men, the stories that are told through Moonlight and Tongues Untied are supremely tender. Both movies focus strongly on the people, the words, the message.

What happens when you allow yourself to love someone and accept love in return?

Not necessarily what happens when people find out.

While the fall out to both of those questions could be violence, the ability for the characters and the audience to suspend their disbelief and to see that in a world that tells someone they aren’t worth love, or their love is wrong, black men loving black men, despite everything, is the revolutionary act. From Chiron’s story that was shaped by a father-figure and his love for his friend, or Marlon Riggs’ final prose where he laments that he was ‘blind to [his] brother’s beauty, but now [he] see[s]… [his] own”, it is critical for these stories to be told.

This narrative, and the counterpublics they speak for, forge opportunities for the future. And you know what? It’s working. 2018 saw the rise of LGBT characters on television, and for the first time, LGBTQ+ characters of colour surpassed their white counterparts 50% to 49% . Gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer, asexual, 2 spirit, and questioning characters of color are being represented on television, film, music, art and media industries.

In fact, just last weekend, Billy Porter became the first openly gay, black man to win an Emmy for Lead Actor in a Drama Series for FX’s groundbreaking show Pose.

As Billy puts it in the final moments of his heartfelt speech:

“We are the people, we as artists are the people that get to change the molecular structure of the hearts and minds of the people who live on this planet. Please don’t ever stop doing that, please don’t ever stop telling the truth.”

While the counterpublics of gay, black men are by no means redundant in 2019, the work that they do is being celebrated, awarded, and understood by the publics outside of their own.

And in that way, black men loving black men on television, in films, in music, and in life is a revolutionary act.

Catherine Squires, “Rethinking the Black Public Sphere: An Alternative Vocabulary for Multiple Public Spheres,” Communication Theory 12.4 (Nov 2002): 446-468.

I really enjoyed reading your blog post as I did mine on the same topic. I noticed how we share similar ideas but were able to branch upon them in different ways. Choosing to talk about the film Moonlight (2017) was a great choice as it is interesting to see a more modernized approach on the struggles of being gay and black. There truly isn’t enough cinema that will focus on such a topic and the issues that come with it. I just find it shocking that when Tongues Untied (1989) was released, it sparked a social and political outbreak yet when Moonlight was released it was considered a powerful “must-see” film. It is a good thing, as the world is becoming more acceptant of the LGBT community, and such films create a positive effect on most of society rather than the negative effect Tongues Untied received.

I liked when you stated, “A black man on TV isn’t the same as a gay, black man on TV, just the same as a gay man in a movie isn’t the same as a black, gay man in a movie.” It reflected the issues I have focused on in my blog. The issue is not just with gay black men being discriminated by straight white men, but also straight black men. I always think to myself, “why are gay white men still treated and looked upon differently than gay black men if they are both queer?” It is because of their colour, so even though they both share the same values, one is slightly more accepted in the world than the other, thus leaving gay black men struggling to find community.

LikeLike